Let the Fire Burn, Jason Osder’s powerful debut documentary, opens with period footage of a soft-spoken boy with two names: Michael Moses Ward and Birdie Africa. Michael was known as Birdie as a child—he was one of several kids raised by a small black liberation group that occupied a Philadelphia row house on Osage Avenue. They called themselves MOVE, and they wanted to live without technology and without government interference. But the group and the city were constantly at odds.

On May 13, 1985, the enmity between MOVE and city officials erupted into one of the worst days in Philadelphia history. Years of demonstrations, clashes, and arrests had finally culminated in a mass eviction order and an hours-long shootout. When the shooting ended in a stalemate, the city made the unthinkable decision to drop a bomb on the MOVE row house. It ignited a raging fire. Michael and one other MOVE member escaped, but 11 others were killed, and 61 homes burned down—a working-class black neighborhood turned to ash.

I’m a year older than Michael Ward, and I also grew up in Philadelphia. I remember watching that terrible fire burn, though I was seeing it on TV, safe in my house in a different part of the city. I remember feeling sad, scared, and confused. My father had campaigned hard for Wilson Goode, who’d been elected as Philadelphia’s first black mayor a year and a half earlier. How could Goode have stood by while the police dropped that bomb, and as that fire burned?

It’s to the credit of Osder’s film that it answers these questions by gradually zeroing in on them. Let the Fire Burn offers an even-handed depiction of the racial conflict that led to the conflagration on Osage Avenue. A 1976 re-election ad for Frank Rizzo, the previous mayor, who had built his reputation by raiding the Black Panthers, called Philadelphia “tortured” and complained that “abandoned homes pockmark the ghetto.” The racism was barely below the surface. MOVE’s extremist views are fully aired in the film, too. In one piece of old tape from the 1970s, a group of small MOVE children, naked and dreadlocked, chant mantras like “Our religion is non-compromising to the conception of insane speculation.” The adults also come across as caring, though. “They didn’t believe in spanking,” Michael says in a deposition taken five months after the fire.

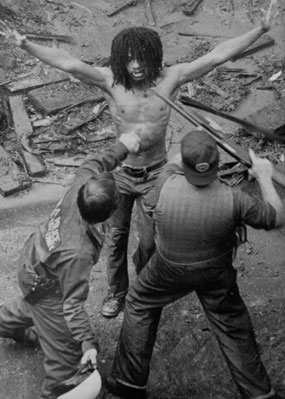

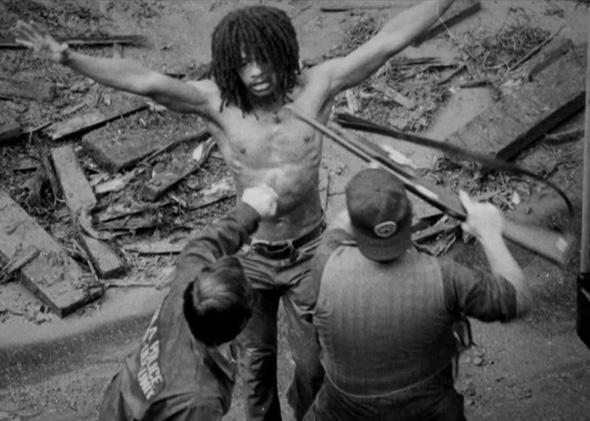

During Rizzo’s tenure, the police department made nearly 200 arrests of MOVE members, often for small street demonstrations. In 1976, six cops were injured in a scuffle with the group that somehow—the details are hazy—caused the death of a 3-week-old baby, Life Africa. After that, it was war. Rizzo promised in 1978 that the police would drag the MOVE members out of their compound “by the back of their necks.” The city turned a huge hoselike weapon called a “deluge gun” on the MOVE house. The confrontation spun out of control, shots were fired on both sides, and a police officer was mortally wounded. Nine MOVE members went to prison for killing him. But when three cops were prosecuted for viciously kicking and beating MOVE member Delbert Africa on the sidewalk—an assault caught on camera—they were found not guilty.

This may sound like a sadly typical-of-the-period case of black extremists versus white city establishment, but it wasn’t that simple. Osder shows that the people complaining the most about MOVE were the group’s neighbors—“ordinary black people,” in the words of City Councilman Lucien Blackwell. By the time Goode was elected in 1983, MOVE had become the scourge of the block. Late at night, loudspeakers blasted curse-laden diatribes from the house. MOVE men walked the sidewalk carrying rifles. They built a fortified rooftop bunker with slits for weapons. “They decided to aggravate the neighbors to force the city’s hand,” a negotiator who tried to work with both sides says on camera.

On May 13, 1985, the enmity between MOVE and city officials erupted into one of the worst days in Philadelphia history. Years of demonstrations, clashes, and arrests had finally culminated in a mass eviction order and an hours-long shootout. When the shooting ended in a stalemate, the city made the unthinkable decision to drop a bomb on the MOVE row house. It ignited a raging fire. Michael and one other MOVE member escaped, but 11 others were killed, and 61 homes burned down—a working-class black neighborhood turned to ash.

I’m a year older than Michael Ward, and I also grew up in Philadelphia. I remember watching that terrible fire burn, though I was seeing it on TV, safe in my house in a different part of the city. I remember feeling sad, scared, and confused. My father had campaigned hard for Wilson Goode, who’d been elected as Philadelphia’s first black mayor a year and a half earlier. How could Goode have stood by while the police dropped that bomb, and as that fire burned?

It’s to the credit of Osder’s film that it answers these questions by gradually zeroing in on them. Let the Fire Burn offers an even-handed depiction of the racial conflict that led to the conflagration on Osage Avenue. A 1976 re-election ad for Frank Rizzo, the previous mayor, who had built his reputation by raiding the Black Panthers, called Philadelphia “tortured” and complained that “abandoned homes pockmark the ghetto.” The racism was barely below the surface. MOVE’s extremist views are fully aired in the film, too. In one piece of old tape from the 1970s, a group of small MOVE children, naked and dreadlocked, chant mantras like “Our religion is non-compromising to the conception of insane speculation.” The adults also come across as caring, though. “They didn’t believe in spanking,” Michael says in a deposition taken five months after the fire.

During Rizzo’s tenure, the police department made nearly 200 arrests of MOVE members, often for small street demonstrations. In 1976, six cops were injured in a scuffle with the group that somehow—the details are hazy—caused the death of a 3-week-old baby, Life Africa. After that, it was war. Rizzo promised in 1978 that the police would drag the MOVE members out of their compound “by the back of their necks.” The city turned a huge hoselike weapon called a “deluge gun” on the MOVE house. The confrontation spun out of control, shots were fired on both sides, and a police officer was mortally wounded. Nine MOVE members went to prison for killing him. But when three cops were prosecuted for viciously kicking and beating MOVE member Delbert Africa on the sidewalk—an assault caught on camera—they were found not guilty.

This may sound like a sadly typical-of-the-period case of black extremists versus white city establishment, but it wasn’t that simple. Osder shows that the people complaining the most about MOVE were the group’s neighbors—“ordinary black people,” in the words of City Councilman Lucien Blackwell. By the time Goode was elected in 1983, MOVE had become the scourge of the block. Late at night, loudspeakers blasted curse-laden diatribes from the house. MOVE men walked the sidewalk carrying rifles. They built a fortified rooftop bunker with slits for weapons. “They decided to aggravate the neighbors to force the city’s hand,” a negotiator who tried to work with both sides says on camera.

Comment